“For a tourism-based economy to sustain itself in local communities, the residents must be willing partners in the process. Their attitudes toward tourism and perceptions of its impact on community life must be continually assessed.” - (Allen et al. 1988)

Tourism is a transformative factor of urbanism that has the potential to drive the economy and formal values of a city. Brazil is well noted internationally as an icon of scenic attractions that promotes visitors. Rio de Janeiro actively remains a top contributor to the tourism of Brazil, expanding it up to 104% in the year 2000. As such an influential catalyst for urban development, tourism stirs conflict from the locals that undergo its effects of socio-spatial segregation. If tourism then breeds a society that is in tension with the motives of its government, do locals have the potential to counter these motives through the exploitation of the city’s showcased areas?

Rio de Janeiro, in most recent years, has been the host of high impact mega events that stimulate the desire for its government to recreate the image of the city. Hosting the FIFA World Cup in 2014 was considered a major success in the eyes of its government because of its ability to increase jobs as well as the investments made in its tourist sectors. Hosting the 2016 Olympic Games was also considered a major success because it gave more reason to continue in the revitalization of Rio’s visage. It took 13 billion dollars in order to finance the World Cup and an estimated 20 billion to finance the Olympics. Although these costs included the construction of new infrastructure and revived projects including that of Porto Maravilha, it highly leaned towards the needs of the modern tourist and sacrificed the land of its squatter communities. Prior to the Olympics, President Eduardo Pae claimed the only community demolition that would occur was set to be in Villa Autodromo because of its proximity to the Olympic Park. In reality, 22,059 families have been evicted from their communities due to the prioritization of newly constructed transport that link touristic entities dispersed throughout the city. This control over passages not only included additions like the 2008 Funicular Railway but limited travels for the poorer citizens residing in Northern Rio. This limitation included the removal of bus routes that previously made these tourist attractions accessible to residents living in these informal settlements and they have since been at risk of demolition due to planned infrastructure and real estate projects. Such aggressive and blatant moves has positioned Rio not a good place to live in, but rather a place to invest in. The Pacification Police Units (UPP) was another policy implemented in the informal settlements because of the events in order to control the violence or rather control the territories. All of these tactics were employed through levels of invisible crime, fraud, and bribery in order to skew the realities of Rio for the sake of creating a manicured perception for the temporary visitor.

INVASIVE & HOST SYSTEMS STUDIES: BOTANY_THE STRANGLER FIG

The growth of invasive botany is systemized by its need to survive and in order to survive, it exploits its host(s) at three varying scales. The first is through the inhibition of direct resources or nutrients. The second includes spatial restrictions due to its ability to grow along the host’s formal accentuations. In its maturity, there is then the formulation of a defined territory that inhibits growth of the host but also sustains the reproduction and optimization of the system.

PHASES OF INVASIVE EXPLOITATION VIA STRANGLER FIG SPECIES

UNTOUCHED HOST

INVADER LANDING

INVADER GROWTH

EXTRACTING RESOURCES

FINAL DOMINANCE

SYSTEM EXPANSION AND GROWTH

TAXONOMIES OF GROWTH

TYPOLOGICAL CATALOG: URBAN INVADERS & HOST

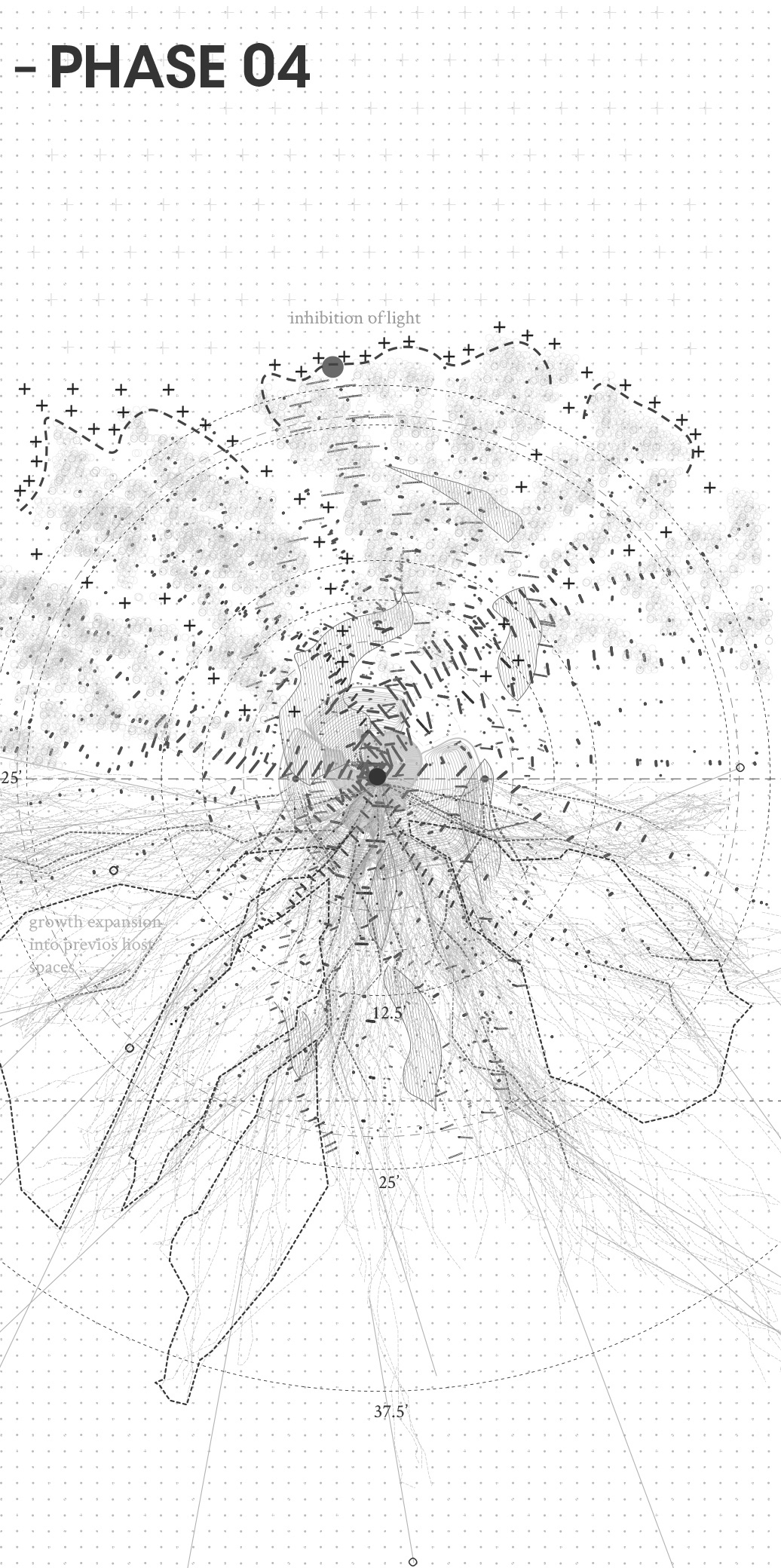

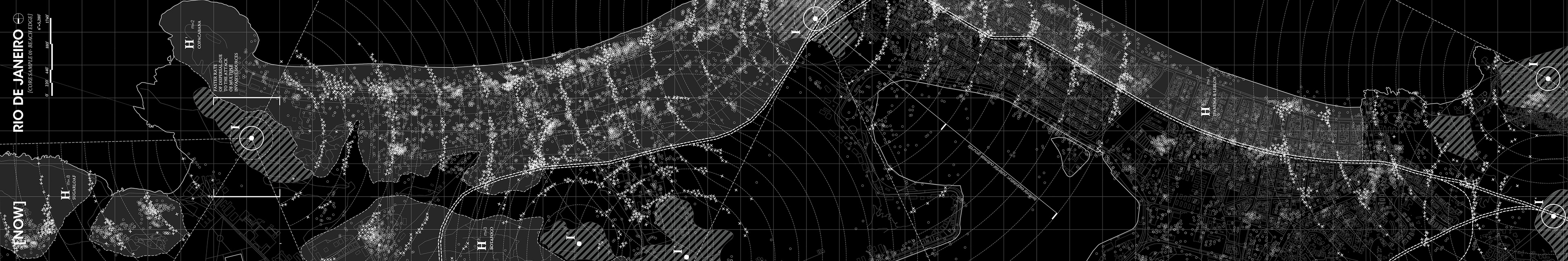

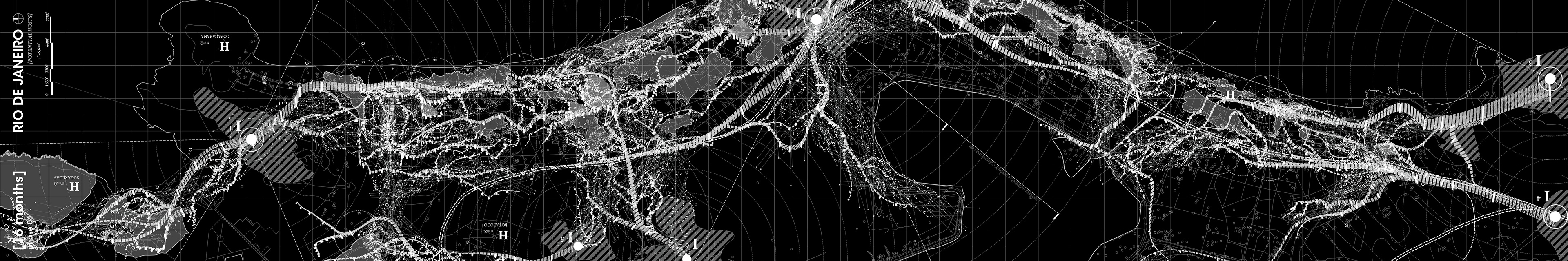

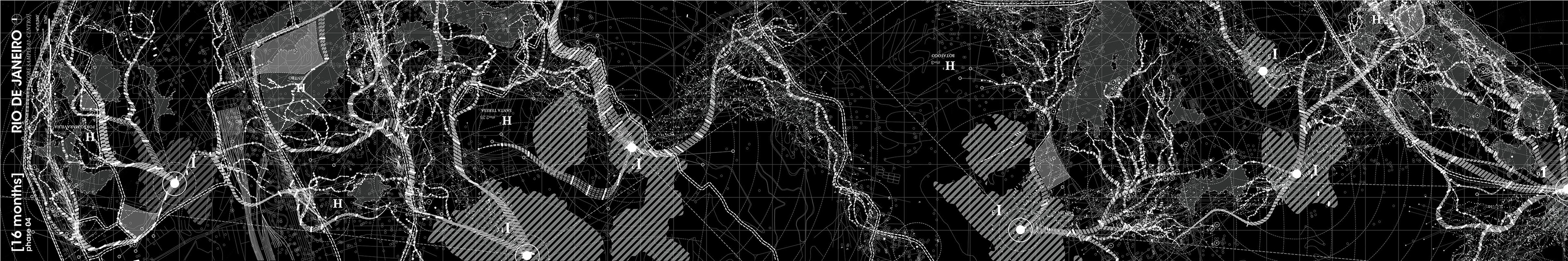

RIO DE JANEIRO_INVADER OUTBREAK MAP

The urban invader has the potential to parasitically transform energy, form, and resources from touristic sites. Parallel to the system within invasive botany, growth is tracked based on the form and magnitude of its host. The system is similarly working to achieve conversion. It works to grow in a non-native land and exploits the occurring living systems as momentary casts to create an environment in which it can thrive. The optimal state for this system is this dominance of not only one host, but rather dominance of a territory.

CORE STRIPS 1, 2, AND 3 TRANSFORMATIONS

CORE STRIP 1_BEFORE

CORE STRIP 1_AFTER

CORE STRIP 2_BEFORE

CORE STRIP 2_AFTER

CORE STRIP 3_BEFORE

CORE STRIP 3_AFTER

By targeting and exploiting these sites of its energy, removing its resources (or monetary values), and inhibiting the further development of form, the degradation of these sites become inevitable. These outbreaks would occur quickly within the time frame of 4 months alongside the season at which tourism levels peak in Brazil. In time, as these seeds of crime disperse and outbreak, the methods in which people populate and activate these spaces has the potential to alter and at the most extreme level, diminish entirely and become occupied by its invaders. The point at which there is complete exploitation, however, eliminates the resources that tourists and the tourist industry offers for such invaders. The question of who these invader counter attacks once there are no more hosts to take over. Do they then attack and conflict in the efforts of dominating one another? Nonetheless, such a domination would destroy the economic power the sites hold for the city of Rio, and thus the spatial hierarchy that comes with it.